Distinguishing between forwards and futures

Earlier, we spoke about futures and compared it to forwards. Just to again highlight the major difference between the two, futures are traded on an exchange while forwards are private agreements between two parties. Because of their OTC nature, forwards are subject to counterparty risk, something which does not exist in case of futures because the trades are guaranteed by the exchange. Tackling the issue of counterparty risk was one of the major reasons that led to the emergence of futures in the US last century.

Let us now try to understand, from a practical standpoint,how forwards and futures differ from each other.

Example of forwards:

Assume that John works for a company that produces crude oil and Ron works for a company that refines crude oil. Both the persons here have differing interests – John is oil producer who will sell crude once it is produced, while Ron is a refiner who will buy crude when needed. For John, the risk is of price declining in the future (as he is a seller of crude); while for Ron, the risk is of price rising (as he is a buyer of crude).

Assume that the current price of crude oil is ₹4000/barrel. In order to safeguard themselves from price risk and uncertainty, the two meet on March 1st and enter into a forward contract wherein John would be selling 1000 barrels of oil to Ron in three months’ time at the current price of ₹4000/barrel, which translates to a total contract value of ₹4 million. As such, the two have locked in the price for crude oil and hedged themselves against price risk. In three months from today i.e. on settlement date, John will receive ₹4 million from Ron in return of delivering 1000 barrels of crude oil to him (we will briefly talk about types of settlement at the end of this discussion).

There are three possible situations that could occur three months from today.

Situation 1 : Price of crude oil drops, say to ₹3800/barrel

In this scenario, the value of 1000 barrels would be ₹3.8 million. But because the two entered into a contract to transact at ₹4 million, they will have to honour it wherein John will receive ₹4 million from Ron. As John is receiving more than the currently prevailing price, he has gained ₹2 lac by entering into a forward contract. On the other hand, Ron has lost ₹2 lac as price moved against him.

Situation 2: Price of crude oil stays unchanged at ₹4000/barrel

In this scenario, the value of 1000 barrels would still be ₹4 million. As both would be transacting at the prevailing market value of ₹4 million, none of them will realize any profit or loss.

Situation 3 : Price of crude oil rises, say to ₹4300/barrel

In this scenario, the value of 1000 barrels would be ₹4.3 million. But because the two entered into a contract to transact at ₹4 million, they will have to honour it wherein John will receive ₹4 million from Ron. As John is receiving less than the currently prevailing price, he has lost ₹3 lac as the price moved against him. On the other hand, Ron has gained ₹3 lac by entering into a forward contract.

The risk over here, however, is one of the two parties defaulting i.e. not fulfilling the contract on the settlement date. For instance, in case of situation 1, Ron, who is on the losing side, may not fulfil his contract of paying ₹4 million to John; while in case of situation 3, John, who is on the losing side, may not fulfil his contract of delivering 1000 barrels of crude oil to Ron.

Keep in mind that on the settlement date, the settlement could be in either physical form or cash form. In case of physical settlement, John and Ron will exchange ₹4 million (Ron will pay to John) and 1000 barrels of crude oil; while in case of cash settlement, just the overall profit/loss would be calculated and settled in cash while there won’t be any exchange of the commodity.

Example of futures:

As we saw above, the biggest problem that forwards face is the likelihood of one of the counterparties defaulting. In order to tackle this issue, futures were introduced in the US, wherein the exchange assumes the counterparty risk and ensures that none of the parties to the trade default. In order to understand how this is done, we will have to discuss about a few concepts, mentioned below:

Initial margin

As discussed in an earlier chapter, this is the amount of money that must be deposited by traders (both buyers and sellers) in order to trade a commodity futures contract. This is usually a certain percent of the total contract value. For instance, at a current price of ₹33,050, the total contract value for MCX gold is ₹33,05,000 (₹33,050 CMP * 100 lot size). If the initial margin on gold is 4%, the trader will have to deposit ₹1,32,200 in order to trade one lot of gold futures.

Marking-to-market (MTM)

This is the amount that is adjusted at the end of each trading session to account for a trader’s profit or loss. In case of profit, the amount is credited to the trader’s margin account; while in case of loss, it is debited from the trader’s account.For instance, assume that two parties transact gold futures at ₹33,050. If at the end of the session, gold closes at ₹33,200, the trader would had gone long would gain ₹15,000 (₹150 profit * 100 lot size), while a trader who had gone short would lose ₹15,000. This amount would be credited to the long trader’s margin account at the end of the day and debited from the short trader’s account.MTM ensures that neither party to the trade defaults.

Maintenance margin

This is the minimum amount that must always be kept in the margin account by the trader. Usually, this is a certain percent of the total contract value. The objective of maintenance margin is to ensure that a trader’s account is adequately funded to meet the daily MTM requirements. Think of maintenance margin as the minimum balance that a bank requires its depositors to maintain in their savings account. Continuing with our example from the initial margin section, we saw that if the initial margin was 4%, the trader would need ₹1,32,200 to trade a lot of gold futures. If maintenance margin were set at 3%, after entering a trade, the exchange would require a trader to maintain at least ₹99,150 (₹33,05,000 * 3%) in his account. If after a few days, the margin in a trader’s account drops below ₹99,150, the trader would be required to deposit funds into his margin account to bring back the balance to at least the maintenance margin level.

Let us now understand this discussion with an example.

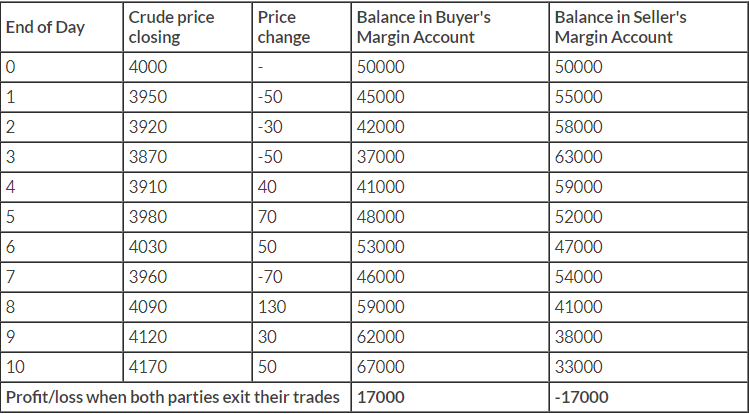

Assume that MCX crude futures March contract is currently trading at ₹4,000 per barrel. Given the lot size of 100 and an initial margin of, say, 4%, a buyer and a seller would each need ₹16,000 to trade one lot of crude futures contract. If maintenance margin were, say, 3%, they would always need to keep at least ₹12,000 in their account to meet the MTM requirements. Let us also assume that each of them starts with ₹50,000 in their margin account (Note that for the sake of simplicity, other costs such as brokerage and tax are not included in the transaction).

Observe how MTM adjustment takes place at the end of each trading session. The overall ₹17,000 gain (loss) that the buyer (seller) makes is not credited (debited) when he exists his position, but rather the profits/losses are adjusted at the end of each day until he closes out his position. If at any point in time, the balance in a trader’s account falls below the maintenance margin level, he will have to deposit funds into his account before the next session to continue trading the commodity. Initial margin, MTM, and maintenance margin are tools that help safeguard the interest of market participants in the futures segment, thereby helping avoid the risk of defaults. Contrast this to forward contract, where settlement occurs only at the end of the contract period, thereby leaving one exposed to counterparty default risk.

Just like forward contracts, futures contracts can be cash settled or by way of physical delivery depending on the commodity in question. The daily MTM takes place at the end of each trading session, while the final settlement takes place at the end of the contract period i.e. on the expiry day at a price known as the settlement price.

Summing it up

So, summing thingsup, forward contracts are settled at the end of the contract period; while futures contracts are settled daily until the position is exited or the contract expires, which ever is earlier. This feature of futures contract makes them less vulnerable to the likelihood of defaults from either of the counterparties. Once again, the table below highlights the key differences between forward and futures contracts.

| Futures | Forwards |

| Exchange traded contracts | Private contracts between two parties |

| Standardized contracts | Customized contracts |

| No element of counterparty risk | Element of counterparty risk |

| Settled every day (mark-to-market) | Settled at the end of the contract |

| Highly regulated instruments | Less regulated instruments |

Distinguishing between futures and options

In our earlier topic, we briefly talked about options. Restating again, a commodity options contract is a contract that gives the buyer (the holder of the option) the right, but not an obligation, to buy or sell a commodity at a specific time in the future for a specific price, called the strike price or the exercise price. To understand the basics terminologies of options, kindly refer to chapter 1.

In terms of similarity, both futures and options are traded on an exchange and are standardized derivative contracts. However, there are a few noteworthy differences between the two. In case of futures, both buyers and sellers are obligated to honour their respective contracts i.e. the buyer is obligated to buy the asset at a specified date and price, while the seller is obligated to sell the asset at a specified date and price (note that buyers and sellers can exit their positions prior to the expiry of the futures contract, if they want to). On the other hand, in case of options, the buyer has the right but not an obligation to buy or sell the asset in the future; while the seller has the obligation to fulfil the contract in case the buyer exercises the right to buy or sell the asset. Another key difference is in terms of the payoff. While futures have unlimited profit/loss potential, options payoff are slightly different. The buyer’s profit is unlimited, and loss is limited to the extent of the premium paid; while the seller’s profit is limited to the extent of the premium received, and loss is potentially unlimited.The table below highlights these differences.

| Futures | Options |

| Buyer has an obligation to honour the contract | Buyer has a right, but not an obligation to honour the contract |

| Seller has an obligation to honour the contract | Seller has an obligation to honour the contract, if the buyer exercises his right to do so |

| Profit potential for a buyer is unlimited | Profit potential for a buyer is unlimited |

| Profit potential for a seller is unlimited | Profit potential for a seller is limited to the extent of premium received |

| Buyer is exposed to unlimited risk | Buyer is exposed to risk that is limited to the extent of premium paid |

| Seller is exposed to unlimited risk | Seller is exposed to unlimited risk |

Example of options:

As already discussed in the first chapter, a call buyer has a bullish view on the underlying, while a call seller has a bearish view. On the other hand, a put buyer has a bearish view on the underlying, while a put seller has a bullish view.

We also saw that for a call buyer, the breakeven point is strike price + premium paid by the buyer. A buyer would start earningprofit on his long call only when the value of the underlying goes above the breakeven point. Until then, he would not be making money. On the other hand, the seller would get to keep his premium as long as the underlying is trading below the breakeven point. Once the underlying goes above the breakeven point, the seller will start making losses. Similarly, for a put buyer, the breakeven point is strike price - premium paid by the buyer. A buyer would start earning profit on his long put only when the value of the underlying goes below the breakeven point. Until then, he would not be making money. On the other hand, the seller would get to keep his premium as long as the underlying is trading above the breakeven point. Once the underlying goes below the breakeven point, the seller will start making losses.

Let us understand this with a simple example.At the time of writing, Gold March 33000 put is trading at ₹450. As this is a put option, the buyer would profit only when the price drops below the breakeven point, which is 32550 (33000 strike price – 450 put premium). As long as the underlying is trading above the breakeven point, the buyer won’t exercise his right to sell and as such, the seller will get to keep the premium. Similarly, Gold March 33000 call is trading at ₹125. As this is a call option, the buyer would profit only when the price rises above the breakeven point, which is 33125 (33000 strike price + 125 call premium). As long as the underlying is trading below the breakeven point, the buyer won’t exercise his right to buy and as such, the seller will get to keep the premium.

Payoff for futures and options

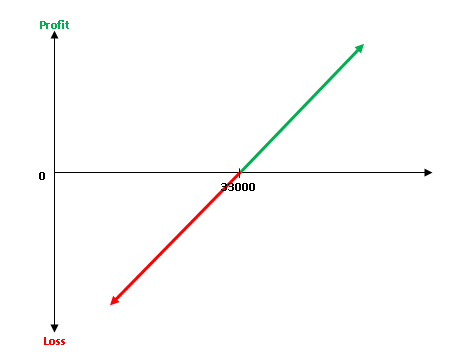

Payoff for long futures: Upward sloping to the right

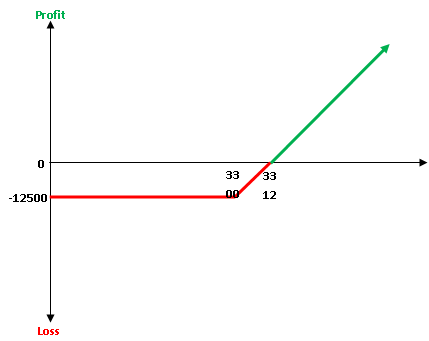

A trader who goes long in futures expects the price of the underlying to go up i.e. he is bullish on the underlying. His profits are unlimited and so are his losses. The graph below shows the payoff chart for a trader who has gone long on 1 lot of gold futures at ₹33,000

The horizontal axis (X-axis) represents the various price possibilities on expiry, while the vertical axis (Y-axis) represents the profit/loss per lot of gold at various price intervals. The point at which the rising line touches the X-axis is the breakeven point (in this case₹33,000). This is the point where the trader neither makes money nor loses money (for simplicity sake, we are not considering brokerage and taxes in our calculation). If the price of gold rises above ₹33,000, the trader makes money that is equal to the difference between entry price and current price multiplied by 100 (represented by green line); while if the price drops below ₹33,000, the trader loses money (represented by red line). As can be seen here, the upside is unlimited and so is the downside.

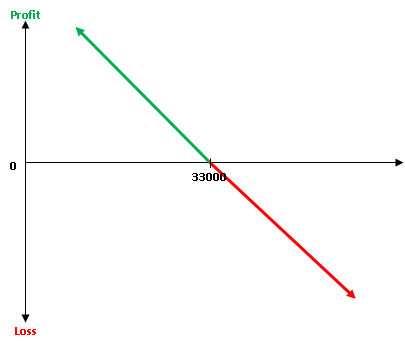

Payoff for short futures: Downward sloping to the right

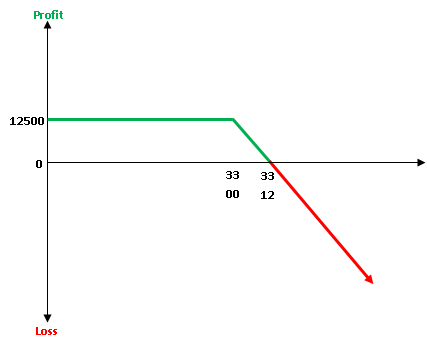

A trader who goes short in futures expects the price of the underlying to go down i.e. he is bearish on the underlying. His profits are unlimited and so are his losses. The graph below shows the payoff chart for a trader who has gone short on 1 lot of gold futures at ₹33,000.

The above chart shows the payoff for a trader who shorts 1 lot of Gold futures on the MCX at ₹33,000. As can be seen, the payoff for a trader who shorts is downward sloping to the right, meaning as the price of the underlying rises, the profitability reduces. The entry level of ₹33,000 is also the breakeven level. Rise beyond this would lead to losses, while a drop below the breakeven level would lead to gains. In case of short futures too, both profits and losses are unlimited.

Payoff for long call option: Gain above BEP, loss below BEP

The above chart shows the payoff for a trader who has bought 1 lot of gold call option having a strike price of ₹33,000 by paying a premium of ₹125. As already discussed earlier, the breakeven point for a call option is strike price + premium paid. In this case, it is ₹33,125. A trader would make a profit on long call option only when the price of the underlying goes above ₹33,125. As can be seen, maximum loss is limited to the extent of premium paid, which is ₹12,500 per lot. If, on expiration, the price of gold is below ₹33,000, the trader would let his option expire worthless, and thereby make a loss of ₹12,500 per lot. If gold expires at, say ₹33,100, the trader would exercise his right to buy gold, in which case hewould make ₹10,000.However, given that he has paid a premium of ₹12,500 per lot, he would still incur a net loss of ₹2,500 per lot. Finally, if gold price expires at, say, ₹34,000, the trader would exercise his right to buy gold, in which case he will make a net gain of ₹87,500 per lot ({₹34,000 - ₹33000 - ₹125} * 100). So, as we can see, maximum loss is limited to the extent of premium paid, but maximum profit is potentially unlimited.

Payoff for short call option: Gain below BEP, loss above BEP

The above chart shows the payoff for a trader who has sold 1 lot of gold call option having a strike price of ₹33,000 ata premium of ₹125. A trader would profit on the short call option as long as the price of the underlying is below ₹33,125, which is the breakeven point. As can be seen, maximum profit is limited to the extent of premium received, which is ₹12,500 per lot. If, on expiration, the price of gold is below ₹33,000, the trader who has sold a call option would get to keep the entire premium of ₹12,500 as the buyer of the call option would not exercise his right to buy the underlying. If gold expires at, say ₹33,100, the buyer would exercise his right to buy gold, in which case the seller’s profit would reduce to ₹2,500 per lot (₹12,500 - {₹33,100 - ₹33,000} * 100). Finally, if gold price expires at, say, ₹34,000, the buyer would exercise his right to buy gold, in which case the seller’s loss will mount to ₹87,500 per lot ([₹125 - {₹34,000 - ₹33,000}] * 100). So, as we can see, maximum profit is limited to the extent of premium received, but maximum loss is potentially unlimited.

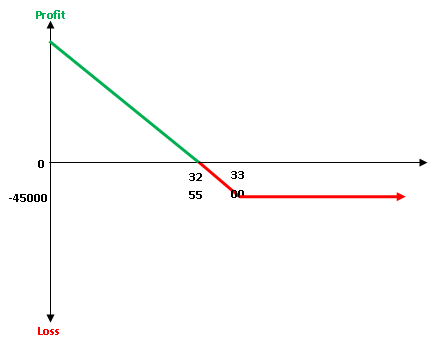

Payoff for long put option: Gain below BEP, loss above BEP

The below chart shows the payoff for a trader who has bought 1 lot of gold put option having a strike price of ₹33,000 by paying a premium of ₹450. The breakeven point for a put option is strike price - premium paid. In this case, it is ₹32,550. A trader would make a profit on long put option only when the price of the underlying goes below ₹32,550. As can be seen, maximum loss is limited to the extent of premium paid, which is ₹45,000 per lot. If, on expiration, the price of gold is above ₹33,000, the trader would let his option expire worthless, and thereby make a loss of ₹45,000 per lot. If gold expires at, say ₹32,700, the trader would exercise his right to sell gold, in which case he would make ₹30,000. However, given that he has paid a premium of ₹45,000 per lot, he would still incur a net loss of ₹15,000 per lot. Finally, if gold price expires at, say, ₹32,000, the trader would exercise his right to sell gold, in which case he will make a net gain of ₹55,000 per lot ({₹33,000 - ₹32,000 - ₹450} * 100). So, as we can see, maximum loss is limited to the extent of premium paid, but maximum profit is potentially unlimited.

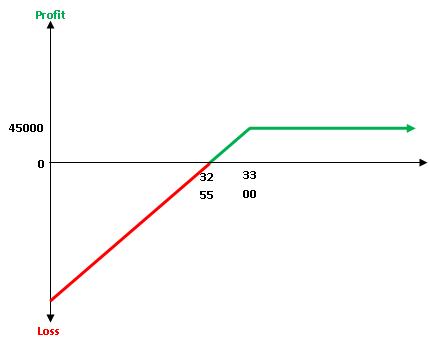

Payoff for short put option: Gainabove BEP, loss below BEP

The above chart shows the payoff for a trader who has sold 1 lot of gold put option having a strike price of ₹33,000 at a premium of ₹450. A trader would profit on the short put option as long as the price of the underlying is above ₹32,550, which is the breakeven point. As can be seen, maximum profit is limited to the extent of premium received, which is ₹45,000 per lot. If, on expiration, the price of gold is above ₹33,000, the trader who has sold the put option would get to keep the entire premium of ₹45,000 as the buyer of the option would not exercise his right to sell the underlying. If gold expires at, say ₹32,700, the buyer would exercise his right to sell gold, in which case the seller’s profit would reduce to ₹15,000 per lot (₹45,000 - {₹33,000 - ₹32,700} * 100). Finally, if gold price expires at, say, ₹32,000, the buyer would exercise his right to sell gold, in which case the seller’s loss will mount to ₹55,000 per lot ([₹450 - {₹33,000 - ₹32,000}] * 100). So, as we can see, maximum profit is limited to the extent of premium received, but maximum loss is potentially unlimited.

Summing it up

As we saw above, in case of futures, the profit/loss potential are unlimited on either side of the breakeven point. Meanwhile, in case of options, the buyer’s profit potential is unlimited, while risk is limited to the extent of premium paid; whereas the seller’s profit is limited to the extent of premium received, while risk is potentially unlimited.

Some formulas that are worth remembering are mentioned below:

For call option

- If underlying price is above the strike price, profit for buyer = (underlying price –strike price – premium) * lot size; while loss for seller = (premium – {underlying price – strike price}) * lot size

- If underlying price is below the strike price, loss for buyer = premium paid; while profit for seller = premium received

- Breakeven price = strike price of call option + call premium

For put option

- If underlying price is below the strike price, profit for buyer = (strike price – underlying price – premium) * lot size; while loss for seller = (premium – {strike price – underlying price}) * lot size

- If underlying price is above the strike price, loss for buyer = premium paid; while profit for seller = premium received

- Breakeven price = strike price of put option – put premium

Hedging using futures

Earlier, we talked about some of the basic concepts related to futures such as initial margin, MTM, and maintenance margin. We discussed how the various calculations take place right from the time the futures contract is initiated until the time it is exited. Going back to the crude example we talked earlier in this chapter, we saw that a trader who buys 1 lot of crude oil futures would profit ₹17,000 if oil prices go up from ₹4,000 to ₹4,170. This profit of ₹17,000 per lot is not credited at the time when the trader exits his position, but rather profits and losses are adjusted everyday to ensure that no defaults occur at the time of exiting the position. The overall profitability would essentially be the same as it is in the case of forward contracts, just the timing of the payoff would be different (adjusted at the end of every trading session in futures as against adjusted at the time of exiting the position in forwards).

Now, we will talk about how futures can be used to hedge a position that a trader could have in the underlying asset. As we know by now, the objective of hedging is to reduce risk as much as possible. Hedging is usually done by producers of commodities as well as by consumers of commodities. For a producer, the primary risk is of thecommodity price declining in the future, which would have a negative impact on the producer’s revenue. For instance, if gold price today is ₹33,000 per 10 grams and if a producer is expected to deliver, say, 1000kgs of the metal 3 months down the line, his profitability would be impacted if price of gold drops below₹33,000 at the time of delivery. Similarly, for a consumer, the primary risk is of price rising in the future, which in turn would raise the consumer’s costs. For instance, if gold price today is ₹33,000 and if a jeweller needs, say, 10 kgs of gold 3 months down the line, his profitability would be squeezed if price of gold were to rise above ₹33,000 during this period (the assumption here is the jeweller won’t be able to increase the price of his product).

Both producers and consumers can significantly mitigate the price risk by hedging their underlying exposure in the futures segment. Let us now understand how this can be achieved.

Example 1: Hedging by a commodity producer (short futures)

As already discussed, a commodity producer faces the risk of commodity pricesweakening. In order to safeguard against this, a producer can take an opposite position in the futures segment.Let’s take the case of a company, say ABC Ltd, which mines for and produces gold. Let us assume that ABC has received an order from one of its customers, say XYZ Ltd, to deliver 10 kgs of gold three months from today at the market price that would prevail in three months’ time. Let us also assume that the price of gold futures for delivery in three months is ₹33,000 per 10 grams. As ABC is exposed to lower price risk,it can mitigate this by taking an opposite position in the futures segment i.e. by shorting gold futures.In order to lock in the selling price at ₹33,000, ABC will have to short as much gold in the futures segment as the quantity that it needs to deliver to XYZ in three months.

We know that the trading unit for gold futures on the MCX is 1 kg, which means the lot size is 1 kg. As such, in order to hedge the long exposure in the underlying, ABC will have to short 10 lots of gold futures (given that ABC has gold exposure to the tune of 10 kgs). Assuming an initial margin of 4%, ABC will have to deposit around ₹13.2 lacs in his margin account for initiating the trade in the futures segment. Let us see what happens three months down the line.

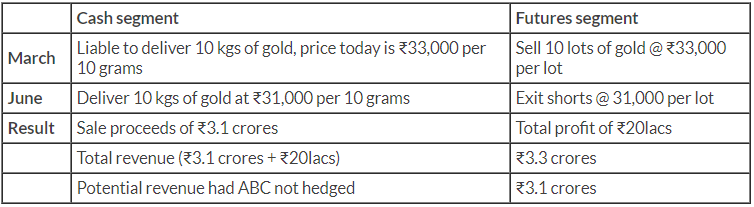

Situation 1: Price of gold drops to ₹31,000 in three months

In this case, ABC will exit his short position in the futures segment at ₹31,000 and thereby profit ₹2 lacs per lot (₹2,000 * 100). So, for 10 lots, the total profit would amount to ₹20lacs. At the same time, ABC will deliver 10 kgs of gold to XYZ at ₹31,000 per 10 grams, for a total value of ₹3.1 crores. Net-net, ABC is gaining₹20lacs from the futures transaction and is earning ₹3.1 crores by delivering gold to XYZ, for a combined inflow of ₹3.3 crores. As can be seen, the total revenue earned by ABC is the same as the price that prevailed three months ago (₹33,000 for 10 grams).

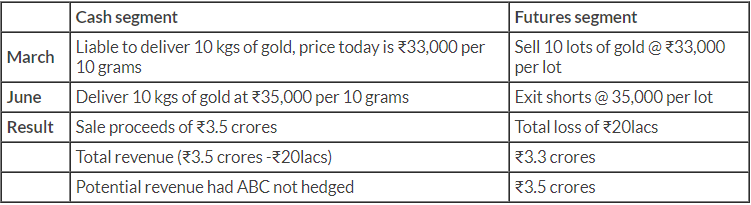

Situation 2: Price of gold rises to ₹35,000 in three months

In this case, ABC will exit his short position in the futures segment at ₹35,000 and thereby lose ₹2 lacs per lot for a total loss of₹20lacs. At the same time, ABC will deliver 10 kgs of gold to XYZ at ₹35,000 per 10 grams, for a total value of ₹3.5 crores. Net-net, ABC is incurring a loss of ₹20lacs from the futures transaction but is earning a revenue of ₹3.5 crores in the cash segment, for a combined revenue of ₹3.3 crores. Again, as can be seen, the total revenue earned by ABC is the same as the price that prevailed three months ago (₹33,000 for 10 grams).

In both the situations, ABC has earned a combined revenue of ₹3.3 crores and has thereby hedged itself against price risk. Situation 1 benefited ABC as it prevented it from earning a lower revenue due to the decline in gold price over three months (without hedging, ABC’s total revenue would have shrunk to ₹3.1 crores). However, situation 2 turned out to be detrimental as it prevented ABC from making a gain due to the rise in gold price over three months (without hedging, ABC’s total revenue would have increased to ₹3.5 crores).

Example 2: Hedging by a commodity consumer (long futures)

A commodity consumer, on the other hand, faces the risk of commodity prices rising. In order to safeguard against this, a consumer can take an opposite position in the futures segment. Let’s now take the case of a jeweller, say PQR, who makes gold ornaments and sells them to end consumers. Let us assume that PQR receivesstrong orders for gold jewellery during Diwali, which is five months away from today. Based on past data, PQRanticipates that it will need 10 kgs of gold three months from today at the market price that would prevail in three months’ time. Let us also assume that the price of gold futures for delivery in three months is ₹33,000 per 10 grams. In order to mitigate price risk,PQR can take an opposite position in the futures segment i.e. by going longon gold futures. To lock in the price at ₹33,000, PQR will have to go longon 10 lots of gold futures (given that it has gold exposure to the tune of 10 kgs). Let us see what happens three months down the line.

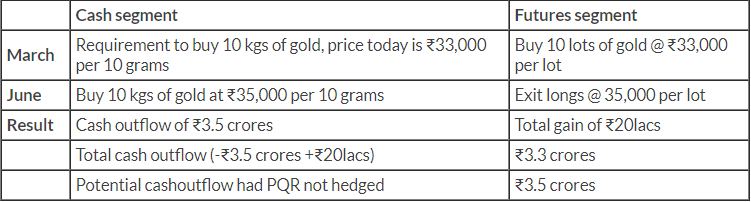

Situation 1: Price of gold rises to ₹35,000 in three months

In this case, PQR will exit his long position in the futures segment at ₹35,000 and thereby gain ₹2 lacs per lot for a total gain of ₹20lacs. At the same time, PQR will buy 10 kgs of gold at ₹35,000 per 10 grams, for a total cost of ₹3.5 crores. Net-net, PQR is gaining₹20lacs from the futures transaction and is buying goldby paying₹3.5 crores in the physical markets.As such, PQR’soverallcosthas come down to ₹3.3 crores. Again, as can be seen, the total cost of buying is the same as the price that prevailed three months ago (₹33,000 for 10 grams).

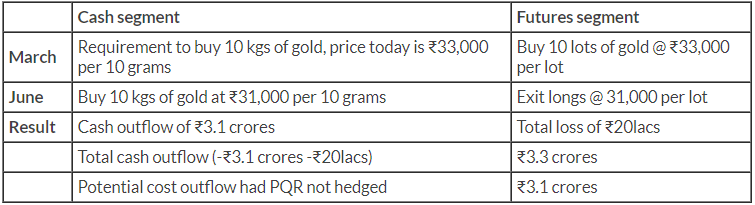

Situation 2: Price of gold drops to ₹31,000 in three months

In this case, PQR will exit his long position in the futures segment at ₹31,000 and thereby lose₹2 lacs per lot for a total loss of ₹20lacs. At the same time, PQR will buy 10 kgs of gold at ₹31,000 per 10 grams, for a total cost of ₹3.1 crores. Net-net, PQR is able to buy gold by paying ₹3.1 crores in the physical markets but it is losing₹20lacs from the futures transaction, raising its combined costto₹3.3 crores. As can be seen, the total costof buying is the same as the price that prevailed three months ago (₹33,000 for 10 grams).

Again, in both the situations, PQR has paid a total of ₹3.3 crores and has thereby hedged itself against price risk. Situation 1 benefited PQR as it prevented it from paying more due to the rise in gold price over three months (without hedging, PQR’s total cost would have risen to ₹3.5 crores). However, situation 2 turned out to be detrimental as it prevented PQR from making a gain due to the fall in gold price over three months (without hedging, PQR’s total cost would have reduced to ₹3.1 crores).

Hedging using options

As we saw in the above section, hedging using futures has both merits and drawbacks. The merit is that hedging using futures prevents downside risks to the concerned participants. For instance, a short hedge prevents a participant from incurring losses in case the price of an underlying goes down; while a long hedge prevents a participant from incurring losses in case the price of an underlying goes up. That said, hedging using futures can also have drawbacks if price does not behave as expected. For instance, a participant who has initiated a short hedge would see his profitability reduce in case the price of the underlying goes higher; while a participant who has initiated a long hedge would suffer in case the price of the underlying goes lower. We saw this in each of the two examples above. Put it in another way, short hedge using futures protects a participant from downside risk, but it also closes the door for any gains in case price of the underlying goes higher. Similarly, long hedge using futures protects a participant from upside risk, but it also closes the door for any gains in case price of the underlying goes lower.

Options, on the other hand, can offer more possibilities to the participants than do futures. As we already knowby now, buying an option requires the payment of a premium upfront, called the option price. This is the maximum that the participant stands to lose (unlike futures where losses can be unlimited). Buying an option not only protects the participant from adverse price movement, but it also enables a participant to stand a chance of gaining in case of favourable price movement. Contrast this to futures, which protects a participant from adverse price movement, but also prevents a participant from gaining in case of favourable price movement. Let us now understand the concept of hedging using options using a few examples.

Hedging by buying options (insurance strategy)

Example 1: Hedging by a commodity producer (long put option)

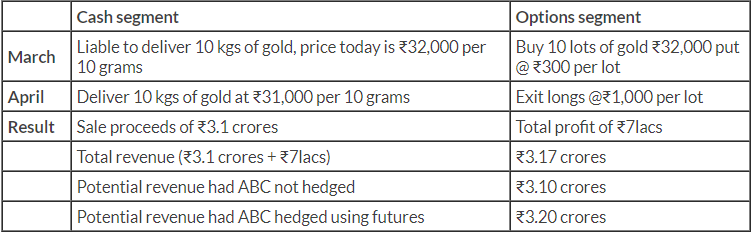

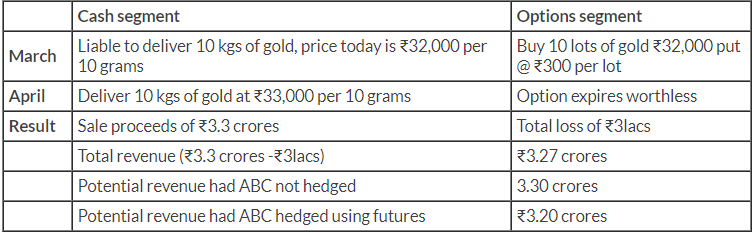

Let’s again take the case of a company, say ABC Ltd, which mines for and produces gold. Let us assume that ABC has received an order from one of its customers, say XYZ Ltd, to deliver 10 kgs of gold one month from today at the market price that would prevail in one months’ time. Let us also assume that the price of gold futures for delivery in one month is ₹32,000 and that the price of a gold put option having a strike price of ₹32,000 is ₹300 (notice here that we are buying anATM put option). As ABC is exposed to lower price risk, it can mitigate this buying gold put option. As ABC has exposure to the tune of 10 kgs, it will have to buy 10 lots of gold put options. At an option price of ₹300, the total premium that ABC will have to pay upfront would be ₹3 lacs (₹300 * 100 * 10). This is the maximum that ABC stands to lose. Let us see what happens in a months’time.

Situation 1: Price of gold drops to ₹31,000 in a month

At expiry, the time value of an option will be zero and as such, the option price would be equal to the intrinsic value of the option (recall that option price = intrinsic value + time value). We know that intrinsic value is the ITM portion of the option. So, in this case, the option price at expiry would be ₹1,000 (₹32,000 strike price - ₹31,000 price at expiry). ABC will exit its long put position at ₹1,000 and thereby profit ₹70,000 per lot ({₹1,000 - ₹300} * 100), for a total profit of ₹7 lacs (₹70,000 * 10). At the same time, ABC will deliver 10 kgs of gold to XYZ at ₹31,000 per 10 grams, for a total revenue of ₹3.1 crores. Net-net, ABC is gaining ₹7 lacs from the options transaction and is earning ₹3.1 crores by delivering gold to XYZ, for a combined inflow of ₹3.17 crores. Without hedging, ABC’s revenue would have stood at₹3.1 crores.

Situation 2: Price of gold rises to ₹33,000 in a month

At expiry, the time value of an option will be zero and as this option is OTM, its intrinsic value will also be zero. As such, the option price would be equal to zero. Hence, ABC will let the option expire worthless and thereby lose the entire amount paid upfront i.e. ₹3 lacs. At the same time, ABC will deliver 10 kgs of gold to XYZ at ₹33,000 per 10 grams, for a total value of ₹3.3 crores. Net-net, ABC is losing₹3 lacs from the options transaction and is earning ₹3.3 crores by delivering gold to XYZ, for a combined inflow of ₹3.27 crores. Now contrast this to futures. Had ABC hedged using futures by shorting gold, his revenue would have stood at ₹3.20 crores. So, as we can see, buying an option not only protects the participant from adverse price movement, but it also enables a participant to stand a chance of gaining in case of favourable price movement.

In the first situation, ABC earned a combined revenue of ₹3.17crores and has thereby hedged itself (to some extent) against price risk. Situation 1 has benefited ABC as it has prevented it from earning a lower revenue due to the decline in gold price in a months’ time (without hedging, ABC’s total revenue would have shrunk to ₹3.1 crores). Situation 2, on the other hand,limited ABC’s gain due to a rise in gold price in a months’ time (without hedging, ABC’s total revenue would have been ₹3.3 crores). Nonetheless, hedging using options enabled ABC to earn a higher revenue than it would have earned had it hedged using futures.

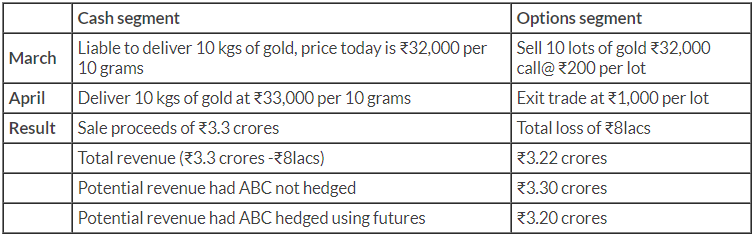

Example 2: Hedging by a commodity consumer (long call option)

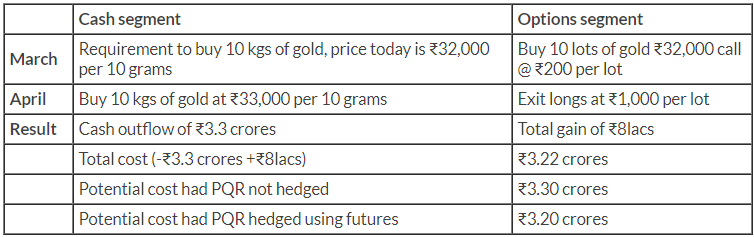

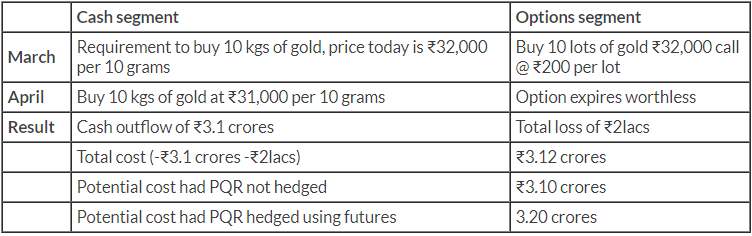

Let’s now take the case of a jeweller, say PQR, who makes and sells gold ornaments to the end consumers. Let us assume that PQR will need 10 kgs of gold in a months’ time at the market price that would prevail then. Let us also assume that the price of gold futures for delivery in a month is ₹32,000 per 10 grams and that the price of a gold call option having a strike price of ₹32,000 is ₹200. As PQR is exposed to higher price risk, it can mitigate this buying gold call options. As PQR has exposure to the tune of 10 kgs, it will have to buy 10 lots of gold call options. At an option price of ₹200, the total premium that PQR will have to pay upfront would be ₹2 lacs (₹200 * 100 * 10). This is the maximum that PQR stands to lose. Let us see what happens in a months’ time.

Situation 1: Price of gold rises to ₹33,000 in a month

At expiry, as the option is ITM, the option price would be equal to its intrinsic value, which is₹1,000 (₹33,000 price at expiry - ₹32,000 strike price). PQR will exit its long call position at ₹1,000 and thereby profit ₹80,000 per lot ({₹1,000 - ₹200} * 100), for a total profit of ₹8 lacs (₹80,000 * 10). At the same time, PQR will buy 10 kgs of gold at ₹33,000 per 10 grams, for a total cost of ₹3.3 crores. Net-net, PQR is gaining ₹8 lacs from options transaction and is paying₹3.3 crores for buying gold from the physical market, for a totaloutflow of ₹3.22 crores. Without hedging, PQR’s cost would have been₹3.3 crores.

Situation 2: Price of gold drops to ₹31,000 in a month

At expiry, the time value of an option will be zero and as this option is OTM, its intrinsic value will also be zero. As such, the option price would be equal to zero. Hence, PQR will let the option expire worthless and thereby lose the entire amount paid upfront i.e. ₹2 lacs. At the same time, PQR will buy 10 kgs of gold at ₹31,000 per 10 grams, for a total cost of ₹3.1 crores. Net-net, PQR is losing ₹2 lacs from the options transaction and is paying₹3.1 crores forbuying gold from the physical market, for a combined outflow of ₹3.12 crores.

As we can see from the above examples, buying an option acts as an insurance policy, wherein the buyer of the option is paying a premium to the seller to acquire the right to buy or sell the underlying asset in the future. Unlike futures however, buying an option not only reduces risk, but it enables the participant to stand a change of gaining in case of a favourable price movement.In the first situation, PQRpaid a total of ₹3.22 crores and has thereby hedged itself against price risk. Situation 1 has benefited PQR as it has prevented it from payingmore due to a rise in gold price in a months’ time (without hedging, PQR’s total cost would have risen to ₹3.3 crores). Situation 2, on the other hand, prevented PQR from paying less due to a drop in gold price in a months’ time (without hedging, PQR’s total cost would have been ₹3.10 crores). Nonetheless, hedging using options enabled PQR to payless than it would have paid had it hedged using futures.

Hedging by selling options (income strategy)

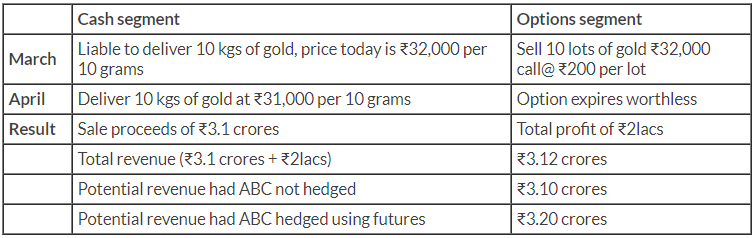

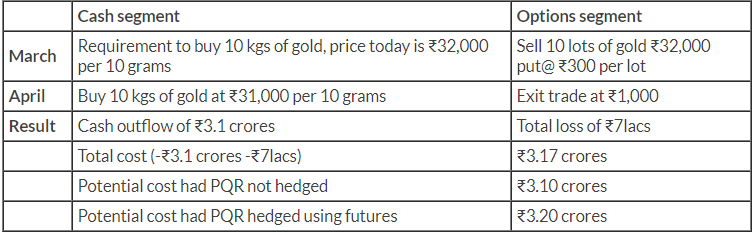

Example 1: Hedging by a commodity producer (shortcall option)

Let’s again take the case of ABC Ltd, which mines for and produces gold. Let us assume that ABC has received an order from XYZ Ltd to deliver 10 kgs of gold one month from today at the market price that would prevail in one months’ time. Let us also assume that the price of gold futures for delivery in one month is ₹32,000 and that the price of a gold call option having a strike price of ₹32,000 is ₹200. As ABC is exposed to lower price risk, it can mitigate this by selling gold call options. As ABC has exposure to the tune of 10 kgs, it will have to sell 10 lots of gold call options. At an option price of ₹200, the total premium that ABC will receive would be ₹2 lacs (₹200 * 100 * 10). This is the maximum that ABC can earn from the options transaction, no matter how lower the price of the underlying goes. Let us see what happens in a months’ time.

Situation 1: Price of gold drops to ₹31,000 in a month

At expiry, the time value of the option will be zero and as this option is OTM, its intrinsic value would also be zero. As such, the option price would be zero and therefore the buyer of the option would let it expire worthless, allowing ABC to keep the entire premium of ₹2 lacs. At the same time, ABC will deliver 10 kgs of gold to XYZ at ₹31,000 per 10 grams, for a total revenue of ₹3.1 crores. Net-net, ABC is gaining ₹2 lacs from the options transaction and is earning ₹3.1 crores by delivering gold to XYZ, for a combined inflow of ₹3.12 crores. Without hedging, ABC’s revenue would have stood at ₹3.1 crores.

Situation 2: Price of gold rises to ₹33,000 in a month

At expiry, the time value of an option will be zero and as such, the option price would be equal to its intrinsic value, which is ₹1,000. As the call is ITM, the buyer of the option would exit the trade at ₹1,000, causing ABC(the seller of the option) tosuffer a loss of₹80,000 per lot ({₹200-₹1,000} * 100), for a total loss of ₹8 lacs. At the same time, ABC will deliver 10 kgs of gold to XYZ at ₹33,000 per 10 grams, for a total revenue of ₹3.3 crores. Net-net, ABC is losing₹8 lacs from the options transaction and is earning ₹3.3 crores by delivering gold to XYZ, for a combined inflow of ₹3.22 crores. Without hedging, ABC’s revenue would have stood at ₹3.3 crores.

In the first situation, ABC earned a combined revenue of ₹3.12 crores and has thereby hedged itself (to some extent) against price risk. Situation 1 has benefited ABC as it has prevented it from earning a lower revenue due to the decline in gold price in a months’ time (without hedging, ABC’s total revenue would have shrunk to ₹3.1 crores). Situation 2, on the other hand, limited ABC’s gain due to a rise in gold price in a months’ time (without hedging, ABC’s total revenue would have been ₹3.3 crores).

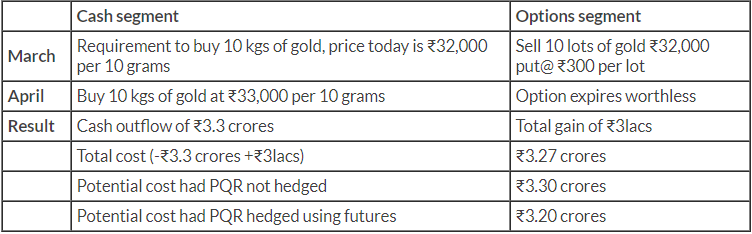

Example 2: Hedging by a commodity consumer (short put option)

Let’s again take the case of the jewellerPQR. Let us assume that PQR will need 10 kgs of gold in a months’ time at the market price that would prevail then. Let us also assume that the price of gold futures for delivery in a month is ₹32,000 per 10 grams and that the price of a gold put option having a strike price of ₹32,000 is ₹300. As PQR is exposed to higher price risk, it can mitigate this selling gold put option. As PQR has exposure to the tune of 10 kgs, it will have to sell 10 lots of gold put options. At an option price of ₹300, the total premium that PQR will have receive is₹3 lacs (₹300 * 100 * 10). This is the maximum that PQR could earn from the option transaction, no matter how higher the price of gold would go in a month’s time. Let us see what happens in a months’ time.

Situation 1: Price of gold rises to ₹33,000 in a month

At expiry, the time value of the option will be zero and as this option is OTM, its intrinsic value would also be zero. As such, the option price would be zero and therefore the buyer of the option would let it expire worthless, allowing PQR to keep the entire premium of ₹3 lacs. At the same time, PQR will buy 10 kgs of gold at ₹33,000 per 10 grams, for a total cost of ₹3.3 crores. Net-net, PQR is gaining ₹3 lacs from the options transaction and is paying₹3.3 crores to buy gold from the spot market, for a combined cost of ₹3.27 crores. Without hedging, PQR’s cost would have been₹3.3 crores.

Situation 2: Price of gold drops to ₹31,000 in a month

At expiry, the time value of an option will be zero and as such, the option price would be equal to its intrinsic value, which is ₹1,000. As the put is ITM, the buyer of the option would exit the trade at ₹1,000, causing PQR (the seller of the option) to suffer a loss of ₹70,000 per lot ({₹300-₹1,000} * 100), for a total loss of ₹7 lacs. At the same time, PQR will buy 10 kgs of gold at ₹31,000 per 10 grams, for a total cost of ₹3.1 crores. Net-net, PQR is losing₹7 lacs from the options transaction and is paying ₹3.1 crores to buy gold from the spot market, for a combined cost of ₹3.17 crores. Without hedging, PQR’s cost would have been ₹3.1 crores.

In the first situation, PQRpaid a total of ₹3.27 crores and has thereby hedged itself against price risk. Situation 1 has benefited PQR as it has prevented it from payingmore due to a rise in gold price in a months’ time (without hedging, PQR’s total cost would have risen to ₹3.3 crores). Situation 2, on the other hand, prevented PQR from paying less due to a drop in gold price in a months’ time (without hedging, PQR’s total cost would have been ₹3.10 crores). Nonetheless, hedging using options enabled PQR to payless than it would have paid had it hedged using futures.

As we can see from the above examples, selling an option is an income strategy, wherein the seller of the option is receiving a premium from the buyer to sell the right to buy or sell the underlying asset in the future.Selling calls to hedge would generate income if the underlying falls in value, but it would also put a cap on gains in case the underlying rises in value. Similarly, selling puts to hedge would generate income if the underlying rises in value, but it would also cap gains in case the underlying falls in value.

Summary

-

Futures are traded on an exchange while forwards are private agreements between two parties. Because of their OTC nature, forwards are subject to counterparty risk, something which does not exist in case of futures because the trades are guaranteed by the exchange.

-

The three elements that reduce the risk of counterparty defaults in futures are: initial margin, marking-to-market, and maintenance margin.

-

Initial margin is the amount of money that must be deposited by traders (both buyers and sellers) in order to trade a commodity futures contract. This is usually a certain percent of the total contract value.

-

Marking-to-market is the amount that is adjusted at the end of each trading session to account for a trader’s profit or loss. In case of profit, the amount is credited to the trader’s margin account; while in case of loss, it is debited from the trader’s account.

-

Maintenance margin is the minimum amount that must always be kept in the margin account by the trader. Usually, this is a certain percent of the total contract value. The objective of maintenance margin is to ensure that a trader’s account is adequately funded to meet the daily MTM requirements.

-

In case of futures, the profit/loss potential are unlimited on either side of the breakeven point. Meanwhile, in case of options, the buyer’s profit potential is unlimited, while risk is limited to the extent of premium paid; whereas the seller’s profit is limited to the extent of premium received, while risk is potentially unlimited.

-

The various options that a commodity producer has in order to hedge his produce are selling futures, buying put options, and selling call options.

-

The various options that a commodity consumer hasin order to hedge his future purchase of the commodity are buying futures, buying call options, and selling put options.

-

Besides these basic strategies, there are several other complex options and futures strategies that commodity producers and consumers can implement to hedge their price risk exposure.

Next Chapter

Comments & Discussions in

FYERS Community

Alok Biswas commented on May 10th, 2019 at 8:39 PM

I feel that there is no much difference between the equity and the commodiy derivatives while trading since both the segments follow the same concepts of Futures and Options. But there should be a reason why most of the traders are nowadays moving to the Commodity trading, what do you feel about it? Is it that the trading time duration which attracts them or something else?

tejas commented on May 14th, 2019 at 5:27 PM

F&O is similar for both equities & commodities but the settlement calendar for commodities is different. Also, the settlement process is physical for most commodities. Commodity trading on the exchanges is still in its nascent stages. Usually, volatility is the precursor to more volumes. In recent times, the movement in crude oil has sparked interest in the minds of those retail traders who had stayed away from commodities for whatever reason.

Dinesh commented on May 13th, 2019 at 1:16 PM

Great Job!. I need to study 2 or 3 times to understand this better. Thanks again for educating us.

tejas commented on May 14th, 2019 at 5:31 PM

Hey Dinesh, Yes please take your time and make sure to understand these concepts well.

pankaj commented on May 29th, 2019 at 5:53 PM

Can you please tell what are the various factors that differentiates hedge funds from mutual funds?

tejas commented on May 29th, 2019 at 7:15 PM

Both are pooled investment vehicles but hedge funds are for the HNIs & Ultra HNIs who can stomach the risks that come along with the high return strategies adopted by hedge funds. Their use of derivatives for hedging and speculation is more complex and apparently not suitable for retail investing community as per the regulators. In India, the minimum investment amount in hedge funds (AIF - 3) is ₹1 crore as on date.

MFs are simpler and more regulated. Their structure is a bit different (Promoter, Trust & AMC). They mostly invest in a portfolio of stocks or bonds as the mandate of the fund mabye. Since MFs handle a lot of retail & public savings, they are more cautious and risk averse in comparison to hedge funds.

Vinayak Joshi commented on June 14th, 2019 at 11:07 PM

Very descriptive explanation about the hedging strategy. Waiting for more strategies in Commodity market in the near future.

tejas commented on June 17th, 2019 at 2:48 PM

Glad you found it useful.

Arnab commented on September 23rd, 2019 at 10:45 PM

Hi,

Your education material on the stock market is fantastic. I'm learning so much from it. Just one request, just like you have given so many examples on hedging in commodity markets, can there be similar examples on equity stock buying along with stock options as hedging purpose, (asking this question if I have managed to grasped the concept correctly that is or is it a wrong question to ask?)

Shriram commented on April 11th, 2020 at 8:36 AM

Hi Arnab, we have been writing on Option Strategies. We suggest you go through this module. Each strategy that is covered under this module has been explained using equity indices and stocks as examples.

Dinesh Kharwar commented on April 10th, 2020 at 7:23 PM

Concept cleared point to point.

Explained in very simple words. Very effective learning. Thanks Fyers.

Shriram commented on April 11th, 2020 at 8:37 AM

Hi Dinesh, thank you for your valuable feedback