The three most important derivative instruments that are transacted around the world are Forwards, Futures, and Options. In this module,we willextensively talk about Futures. We shall talk about various concepts and elements that are related to Futures so that the reader would have a sound knowledge of this versatile instrument and be able to incorporateit for purposes such as trading, hedging, understanding market dynamics etc.

In this introductory chapter, we will talk about the background and the context that led to the emergence of Futures. We will start this chapter by discussing about the history of Derivatives and the purpose why Derivative contracts came into existence. We will also distinguish between the two markets where Derivatives are traded, namely Over-the-Counter (OTC) and on the Exchange. Finally, we will talk about the oldest form of a Derivative contract called Forwards, the problems that these instruments faced, and why these very problems gave birth to Futures.

History of Derivatives

In financial parlance, derivatives are instruments that derive their value from an underlying asset, such asequity, commodity, currency, bond, interest rate, index etc. A derivative contract is an agreement between two (or more) parties to buy or sell the underlying asset at a pre-specified time in the future for a pre-specified price. Each and every detail surrounding the transactionis mentioned in the derivative contract.

The history of derivatives can be tracked back to a few centuries from today when these instruments were used to hedge agricultural supplies as well as those of other commodities. At that time, these were private contracts that were traded over-the-counter i.e. outside of an exchange. The first organized trading took place in the mid-19th century, when the world’s first derivatives exchange was established in 1848 in the United States. This was the Chicago Board of Trade (CBoT), an exchange that is now a part of the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME) group. Back then, the CBoT traded derivatives on agricultural produce such as soybeans, wheat etc.

However, it was not until the 1970s that the real potential of derivatives was unleashed with the introduction of financial derivatives. Over the years, the derivative market has evolved from a billion dollar to a trillion dollar market, with tons of derivative instruments being traded around the world today, both over-the-counter as well as on exchanges.

Purpose of Derivatives

Two of the most common purposes of trading derivatives are:

-

Hedging

-

Speculating

Hedging is an activity wherein one party has an underlying exposure in the spot market and as such, wishes to hedge against the possibility of an adverse price movement in future. The objective of hedging is to reduce price risk as much as possible. The simplest example of hedging is of a farmer, such asa wheat farmer. For a wheat farmer, who cultivates wheat and then sells it in the market, thereis a risk ofthe price of wheat declining from the time of sowing till the time of harvesting. If this happens, the farmer will be forced to sell at a lower price, thereby suffering losses on the crop. In order to safeguard theunderlying position in the spot market, the farmer can hedge his/herexposure by initiating a short position on wheat in the derivatives market (such as entering into a short forward or futures contract on wheat). By doing so, the farmer would lock in a price and thereby hedge the risk to a significant extent. For instance, if the price of wheat falls, then the loss suffered in the physical position (the actual crop) would be mostly offset by the gain made in the derivatives position. The disadvantage, however, is that in case the price of wheat rises, the farmer will not be able to make a gain out of this price rise, as the gain made in the physical position would be mostly offset by the loss suffered in the derivatives position. Hedgers participate in several types of derivatives market such as equity, commodity, currency, bond, intertest rate, index etc.

On the other hand, speculating is an activity wherein the speculator has no underlying exposure in the underlying but is instead trading in derivatives with the sole objective of profiting from a change in the price of the underlying. A speculator is someone who has a view on the market and trades according to that view. For instance, if a person believes that the price of Reliance Industries would rise in the months ahead, he or she could initiate a long position in the derivatives contract of Reliance Industries. If the price of Reliance appreciates as expected, the person would profit; while if the price of Reliance depreciates, the person would suffer a loss. So, as we can see, a speculator is someone who assumes the risk of fluctuation in the price of the underlying for a potential reward.

We will talk in depth about hedging and speculation in a later chapter using Futures contract. For now, just remember that derivatives are used extensively for hedging and speculation.

OTC vs. Exchange-traded Derivatives

There are two places where derivatives are traded:

-

OTC market

-

Exchanges

An OTC market is a decentralized market where trading is carried out electronically between two or more parties. Currency, bond, and interest rate derivatives are heavily traded on the OTC market. As per the needs and requirements of the parties involved, an OTC derivative contract can usually be customized in terms of the size of the contract, the delivery date, the type of the underlying asset, the quality of the underlying asset etc. That said, as OTC derivatives are traded outside of exchanges, they are subject to counterparty risks.

On the other hand, an exchange is a centralized market that is governed by the regulatory authorities of the respective countries. In India, exchange-traded derivatives come under the purview of the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI). An exchange-traded derivative is a standardized contract, because its features are pre-determined by the exchange, such as the size of the contract, the delivery date, the type of the underlying asset, the quality of the underlying asset, margins etc. One of the biggest advantage of an exchange-traded derivative over an OTC derivative is that an exchange-traded derivative is not subject to counterparty risk, as it is governed by the exchange.

The table below shows the key distinctions between an OTC derivative and an exchange-traded derivative:

| OTC Derivative | Exchange-traded Derivative |

| Decentralized, usually traded over the phone | Centralized, traded on exchanges |

| Private contracts | Exchange contracts |

| Customizable contracts | Standardized contracts |

| Counterparty risk exists | Counterparty risk does not exist |

| Traded throughout the day | Traded when exchanges are open |

| Less regulated | Highly regulated |

Forward contract

A forward contract is the oldest type of derivative contract. Put it in simple words, a forward contract is an agreement between two or more parties to buy or sell an underlying asset at some time in the future for a pre-determined price. The buyer of a forward contract assumes a long position in the underlying and is obliged to buy the asset at a specified time in the future for a specified price. On the other hand, a seller of a forward contract assumes a short position in the underlying and is obliged to sell the underlying at a specified time in the future for a specified price. The parties who trade forward contracts do so over-the-counter, rather than on exchanges. Hence, forward contracts are private contracts. Because forward contracts are private contracts, they are customizable. This means the parties to a forward contract can customise the features of the contract in terms of the size, quantity, quality (in case the underlying is a commodity), settlement date, settlement price etc. Having said that, because forward contracts are private contracts, they are subject to counterparty risks. One of the parties stands to lose in case the other defaults from fulfilling the contract on maturity date. Forwards on currencies, fixed income, and interest rates are heavily traded around the world. In fact, the size of the global forward market is much larger than that of the global futures market. Major participants in the forward markets are corporates, banks, and large financial institutions. These instruments, though, are not easily accessible to the retail participants.

Let us present a simple example of hedging using a forward contract. Let us assume that a company is in the business of making gold bars and selling it in the market. Let us say it has received an order from a gold jeweller to deliver 10 kilo grams of gold 3 months down the line. Let us assume that the price of gold in the spot market today is ₹50,000 per 10 grams. The biggest risk that this company faces is that of gold price declining over the course of the next 3 months. This is because if the price of gold drops, the company would realize a lower price from sale proceeds than what the price prevailed when it had received the order. Similarly, a gold jeweller who would be buying 10 kilo grams of gold from that company is also exposed to price risk. For the jewellerthough, the biggest risk is that of price rising over the next 3 months. This is because a rise in the price of goldwould increase the purchasing cost for the jeweller.

As both the gold producing companyand the gold jewellerare exposed to price risk, they can decide to hedge by entering into a forward contract at the prevailing market price of ₹50,000 per 10 grams. So, irrespective of where gold price is 3-months down the line, the gold jeweller would have to pay a total of ₹5 crores (₹50,000/10gms * 10,000gms) to the gold producing company and the latter in turn will have to deliver 10kg gold to the former (in case the two had agreed for a physical settlement). This way, both the gold producing company and the gold jewellerwould have locked in a price for gold today for delivery and payment that is to be made in 3 months’ time.In this case, because the gold producing company is exposed to the risk of price declining, it will assume a short forward position to hedge itself. Similarly, because the gold jeweller is exposed to the risk of price rising, it will assume a long forward position to hedge itself. While the advantage is that both the parties are hedging their price risk and thereby eliminating price uncertainties, the disadvantage is that they are letting go the possibility of a favourable movement in price. So, as we can see, hedging is a trade-off between unfavourable and favourable movement in the price of the underlying. Let us now see how the two parties will be affected by swings in gold price on the maturity date. In fact, let us compare how price risk affects a hedged position and an unhedged position.

Position is hedged (eliminates price risk)

-

If the price of gold rises in three-months’ time to, say, ₹55,000/10gms, the gold producer would stand to lose ₹50 lacs (₹5.5 crores - ₹5 crores) in the forward position while the gold jeweller would stand to gain by the same amount. However, the losses incurred/gains made in the forward position would be completely offset by the corresponding gains made/losses incurred in the underlying position.

-

If the price of gold falls in three-months’ time to, say, ₹46,000/10gms, the gold producer would stand to gain ₹40 lacs (₹5 crores - ₹4.6 crores) in the forward position while the gold jeweller would stand to lose by the same amount. Again, the gains made/losses incurred in the forward position would be completely offset by the corresponding losses incurred/gains made in the underlying position.

-

If the price of gold remains unchanged in three-months’ time, neither parties would gain/lose

So, as we can see from above example, both the parties have managed to mitigate price risk by hedging using forward contracts. We can also see that hedging using forwards is a zero-sum game. This is because one party’s gain would be other party’s loss by the same magnitude.

Position is left unhedged (price risk exists)

-

If the price of gold rises in three-months’ time to, say, ₹55,000/10gms, the gold producer would stand to gain ₹50 lacs (₹5.5 crores - ₹5 crores) while the gold jeweller would stand to lose by the same amount.

-

If the price of gold falls in three-months’ time to, say, ₹46,000/10gms, the gold producer would stand to lose ₹40 lacs (₹5 crores - ₹4.6 crores) while the gold jeweller would stand to gain by the same amount.

-

If the price of gold remains unchanged in three-months’ time, neither parties would gain/lose

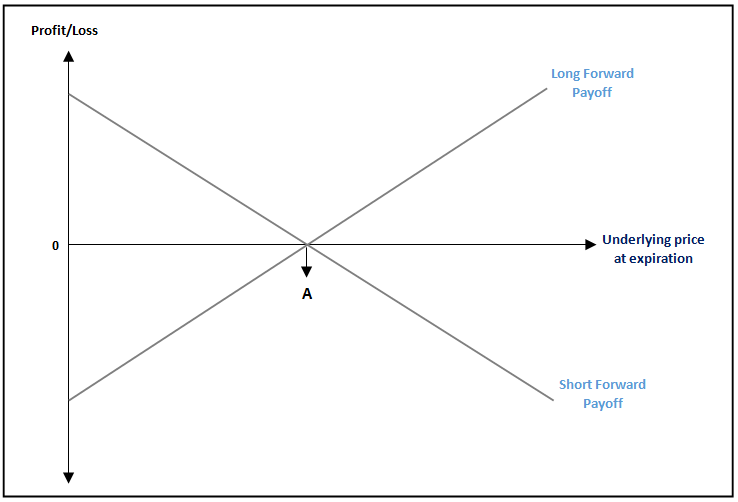

The chart below shows the payoff structure for long as well as short positions in forwards:

In the chart above, the Y-axis is the payoff (profit/loss) line, which hovers above and below zero. Meanwhile, the X-axis represents the price of the underlying security at the expiration of the forward contract. Point A refers to the price at which the contract was entered into by the two parties. Notice that the buyer’s (the gold jeweller in the earlier example) payoff line slopes upwards to the right, with point A being the breakeven point. This is because, as the price moves above point A, the buyer starts making profits in the forward position; and as price moves below point A, the buyer starts incurring losses in the forward position. Similarly, observe that the seller’s (the gold producing company in the earlier example) payoff line slopes downwards to the right, with point A being the breakeven point. This is because, as price moves below point A, the seller starts making profits in the forward position; and as price moves above point A, the seller starts incurring losses in the forward position.

As can be seen from the above graph, forward contracts have a linear payoff. This is because an XXX dollar move in the price of the underlying asset leads to an XXX dollar move in the price of the forward contract as well. Also, the profit and loss potential in a forward contract for both the buyer and the seller is unlimited.

Problems with Forward contracts

Some of the key problems thatforward contracts faced/still face are as mentioned below:

Default risk

One of the major problems that forward contracts face is the risk of counterparty defaulting on its commitment. For instance, consider the earliergold example. On the maturity date, the gold jeweller must pay ₹5 crores to the gold producing company, which in returnhas to deliver 10kg gold to the gold jeweller (assuming the delivery mechanism agreed up on in the forward contract is physical delivery). If, on the maturity date, gold price has declined to ₹45,000, then there could be an outside chance that the gold jeweller may default on the contract and prefer to buy the metal directly from the market itself. In such a case, the gold producing company will suffer. The opposite situation can also arise in case of a price rise.

Difficulty in finding a suitable counter party

This is another problem that a forward contract faces, especially the ones wherein the underlying instrument is not as commonly traded. Remember, forward contracts are private contracts. If you want to hedge a particular underlying, the first thing you need to do is to find out a party who would be willing to take a mirror opposite position to the one you hold. This is certainly not an easy task. Even if you find a counterparty, there could be issues where differences could arise, such as those related to the underlying asset, the size of the contract, the quality of the underlying, settlement date, settlement mechanism etc. Because of such issues, it can sometimes get quite challenging to find a suitable counterparty to the transaction.

Ticket sizes are huge

Usually, if one party wants to enter into a forward contract, he/she would visit a bank or a large financial institution, which usually act as intermediaries between the buyer and the seller of a forward contract. This is especially true in case of commonly traded instruments. These institutions, for a fee, would then be entrusted to find a counterparty to the transaction. However, although forward contracts are customisable, the ticket sizes of entering into such transactions tend to be quite huge, usually amounting to million and billions of dollars. As such, forward contracts are typically not accessible to small market participants, such as retail traders and hedgers. Participants in forward contracts are typically large players such as corporates, banks, financial institutions, money managers etc.

Difficulty in exiting the agreement before maturity

The objective of an activity such as hedging is to safeguard against an adverse move in the price of the underlying asset. But what if the price moves favourably and one of the parties feel that they no longer need a hedge? In such a case, that party would find it really hard to exit the trade before the maturity of the agreement.

All these issues eventually led to the emergence of standardized exchange-traded futures contracts in the 19th century that were governed by various regulatory authorities. And this is precisely the topic of discussion in the next chapter. In Chapter 2, we shall introduce the concept of a futures contract and talk about the various factors associated with these contracts.

Next Chapter

Comments & Discussions in

FYERS Community