16 May, 2025

16 May, 2025

6 mins read

6 mins read

When evaluating companies for investment purposes, many investors focus primarily on metrics like market capitalisation. However, savvier market participants understand that enterprise value (EV) provides a more comprehensive picture of a company's true worth. This metric goes beyond just share price and outstanding shares to account for a company's debt, cash reserves, and other financial elements that impact its overall value. In this blog, we will look at what Enterprise Value is, its components, the working formula and calculation of enterprise value using real world figures.

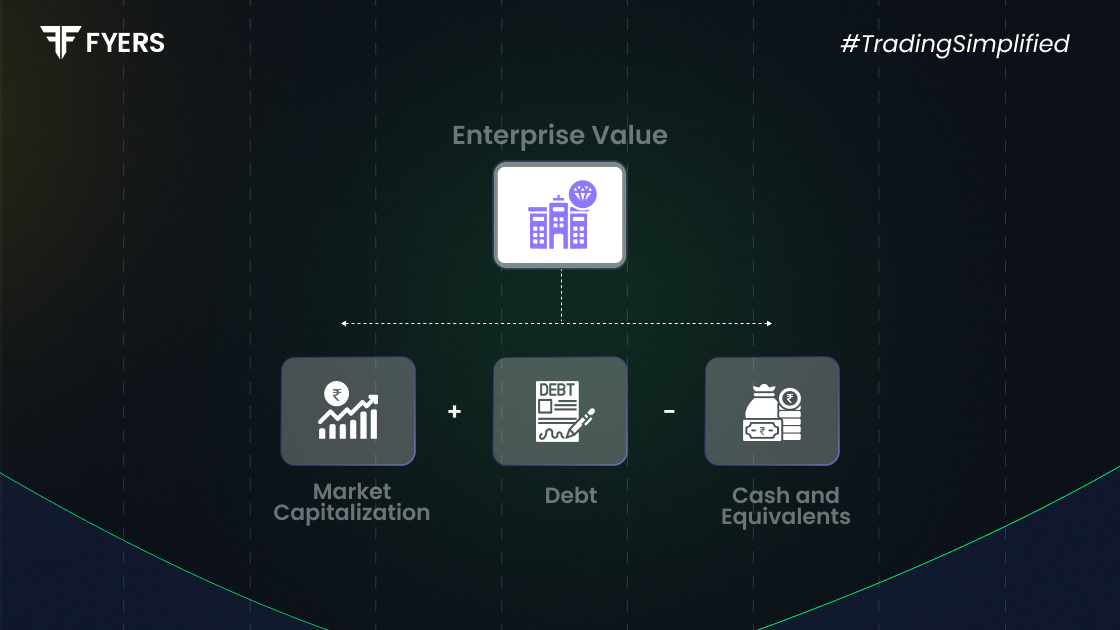

Enterprise Value represents the total value of a company, considering both equity and debt, minus cash and cash equivalents. Unlike market capitalisation, which only reflects the equity portion of a business, EV provides a more complete picture by accounting for all capital sources.

Think of enterprise value as the theoretical takeover price - what it would cost to purchase a company outright. If you were to acquire a business, you'd need to pay the shareholders (market cap) and take on the company's existing debts, but you'd also receive its cash reserves.

To understand this better, imagine you're buying a house worth ₹1 crore. If the house has an outstanding debt of ₹30 lakh, you'd need to pay ₹1 crore to the seller, but you'd also be responsible for the ₹30 lakh debt. The total economic cost to you would be ₹1.3 crore. This comprehensive view is what enterprise value aims to capture in the corporate context.

Enterprise value comprises several key components that collectively represent a company's overall worth. Understanding each of these elements is crucial for accurate financial analysis:

Market capitalisation (market cap) represents the total value of a company's outstanding shares in the market. It's calculated by multiplying the current share price by the total number of outstanding shares.

|

Market Capitalisation = Current Share Price × Total Outstanding Shares |

This component reflects the equity portion of a company's capital structure and what the market currently believes the company's equity is worth.

Total debt includes both short-term and long-term debt obligations of the company:

Short-term debt: Obligations due within one year, including working capital loans, commercial paper, and current portions of long-term debt.

Long-term debt: Obligations due beyond one year, such as term loans, bonds, and debentures.

We add these debt figures when calculating enterprise value because a potential acquirer would assume responsibility for all existing debt.

Preferred shares represent a hybrid security with characteristics of both equity and debt. These shares typically pay fixed dividends and have priority over common shares during liquidation. Their value is added to EV calculations because they represent a claim on the company's assets.

Minority interest refers to the portion of subsidiaries not owned by the parent company but consolidated in financial statements. These represent claims on assets that don't belong to the parent company's common shareholders and are therefore added to the enterprise value.

Cash and cash equivalents include highly liquid assets such as:

Cash in bank accounts

Money market securities

Commercial paper

Short-term government bonds

Treasury bills

Other money market instruments

These assets are subtracted from the enterprise value calculation because they would theoretically offset part of the acquisition cost in a takeover scenario.

The basic formula for calculating enterprise value is:

|

Enterprise Value (EV) = Market Capitalisation + Total Debt + Preferred Shares + Minority Interest - Cash and Cash Equivalents |

Let's break down this calculation with a real-world example using Tata Steel:

Using the example of Tata Steel’s latest figures as of May 2025 for calculation of Enterprise Value

Enterprise Value (EV) = ₹1,82,634 + ₹87,082 + ₹2,093 + ₹0 – ₹8,711 = ₹2,63,098 crore |

Enterprise value serves several critical functions in financial analysis and investment decision-making:

EV offers a more holistic view of a company's worth than market capitalisation alone because it accounts for debt and cash positions. Two companies might have identical market caps but vastly different enterprise values due to their debt loads and cash reserves.

EV facilitates more accurate comparisons between companies with different capital structures. For example:

Company A: ₹500 crore market cap, ₹100 crore debt, ₹50 crore cash

Company B: ₹500 crore market cap, ₹200 crore debt, ₹25 crore cash

Despite having the same market cap, Company A's EV is ₹550 crore, while Company B's EV is ₹675 crore, revealing significant differences in their overall valuations.

EV forms the foundation for key valuation multiples used by analysts:

EV/EBITDA: Enterprise Value to Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation, and Amortisation - measures a company's return on investment

EV/Sales: Enterprise Value to Revenue - useful for valuing companies that aren't yet profitable

EV/FCF: Enterprise Value to Free Cash Flow - indicates how efficiently a company converts its value into free cash flow

These ratios are particularly valuable because they're less affected by differences in capital structures compared to traditional price-based ratios.

In M&A scenarios, enterprise value provides a more accurate picture of the acquisition cost. When one company acquires another, it takes on both the assets and liabilities, making EV the true reflection of the economic cost involved.

A company with a high debt level relative to its market cap might face financial strain, especially during economic downturns or rising interest rate environments. EV helps highlight these potential risks by factoring in debt levels.

While enterprise value offers numerous advantages, it also has some limitations you should be aware of:

EV calculations rely on publicly reported financial data. Any inaccuracies in reported debt levels, cash positions, or minority interests will directly impact the EV calculation. Companies with complex structures or those operating in multiple jurisdictions may present particular challenges.

Financial statements are published periodically, while share prices change daily. This temporal mismatch can lead to enterprise value calculations that don't perfectly reflect current reality, especially for companies with rapidly changing balance sheets.

Traditional EV calculations may not fully account for significant off-balance-sheet obligations like operating leases or underfunded pension liabilities. These items represent future financial obligations but might not be fully reflected in the standard EV formula.

Different industries have unique characteristics that may require adjustments to the standard EV formula. For example:

Banking sector: Financial institutions have complex balance sheets where debt might actually represent inventory rather than financial leverage

Capital-intensive industries: Companies with significant depreciation expenses might warrant special consideration

Regulated industries: Regulatory capital requirements can affect how we should interpret debt levels

For multinational corporations, currency fluctuations, varying accounting standards, and complex international tax structures can complicate enterprise value calculations and comparisons.

Understanding enterprise value and its components gives you a powerful tool for evaluating companies more comprehensively than using market capitalisation alone. Whether you're comparing investment opportunities, analysing potential acquisition targets, or simply trying to determine if a stock is fairly valued, EV provides critical insights into a company's true economic worth. By accounting for debt, cash, and other capital components, enterprise value helps you make more informed investment decisions.

Enterprise value is important because it provides a more comprehensive measure of a company's total value than market capitalisation alone. It accounts for debt obligations and cash positions, giving investors a clearer picture of what it would actually cost to acquire the entire business. This makes it particularly useful for comparing companies with different capital structures and forming the basis for key valuation multiples like EV/EBITDA, helping investors make more informed decisions.

There's no universal "good" enterprise value – what's considered good depends on comparison with industry peers and the company's financial metrics. Analysts typically evaluate relative values through multiples such as EV/EBITDA and EV/Revenue. Lower EV/EBITDA values (below 10) might indicate potential undervaluation, while higher values could suggest overvaluation or high growth expectations. A "good" enterprise value is reasonable relative to the company's earnings potential, growth prospects, and industry standards.

Yes, Enterprise Value (EV) can be negative, though rare. This happens when a company's cash exceeds its market cap, debt, preferred shares, and minority interest. It may suggest the market sees poor value creation, doubts management's use of cash, or is undervaluing the firm—sometimes offering investment opportunities during downturns.

The standard formula for enterprise value is:

EV = Market Capitalisation + Total Debt + Preferred Shares + Minority Interest - Cash and Cash Equivalents

Where:

Market Capitalisation = Current Share Price × Outstanding Shares

Total Debt = Short-term Debt + Long-term Debt

Some analysts make additional adjustments for pension liabilities, operating lease obligations, and other factors to provide an even more accurate representation of a company's true economic value.

Calculate your Net P&L after deducting all the charges like Tax, Brokerage, etc.

Find your required margin.

Calculate the average price you paid for a stock and determine your total cost.

Estimate your investment growth. Calculate potential returns on one-time investments.

Forecast your investment returns. Understand potential growth with regular contributions.